Renewal plan for Hong Kong’s ‘Little Thailand’ leaves long-time residents torn over losing deep community ties

- As URA project draws near, affected residents and businesses hope they can be relocated together

- New homes, commercial premises coming up in area popular with Thai, Chiu Chow communities

Water seeps through the wall, the broken back door does nothing to block the sound of barking stray dogs and, frequently, rats and cockroaches scuttle across the floor. This flat in Hong Kong’s Kowloon City has been home to Wareerat Kanchat for 16 years.

“I have lived here for so long, I can’t imagine a life elsewhere,” says the 60-year-old, who left her native Thailand for Hong Kong in 1993 to work as a domestic helper after her husband died.

Wareerat shares the three-bedroom flat in a dilapidated tenement building along Kai Tak Road with her two adult sons, a daughter-in-law and a colleague from a nearby Thai grocery shop where she works. They pay a monthly rent of about HK$6,000 (US$771).

Aside from knowing her Thai and Hongkonger neighbours well, she says she feels connected to her roots living in the area which is known as “Little Thailand” for its big Thai community.

She patronises the Thai shops and restaurants, and joins other Thais to pray and offer food to Buddhist monks who visit the neighbourhood. She looks forward to the Thai New Year festival of Songkran every April, when a parade winds its way through the streets and everyone takes part in playful water fights.

However, a looming urban redevelopment project threatens to dismantle Hong Kong’s biggest Thai community. Thais such as Wareerat and her friends, as well as Hongkongers who have been long-time residents and business owners are worried they will have to leave.

They and urban studies experts are urging authorities to help preserve the tight-knit community by relocating those affected within the same district.

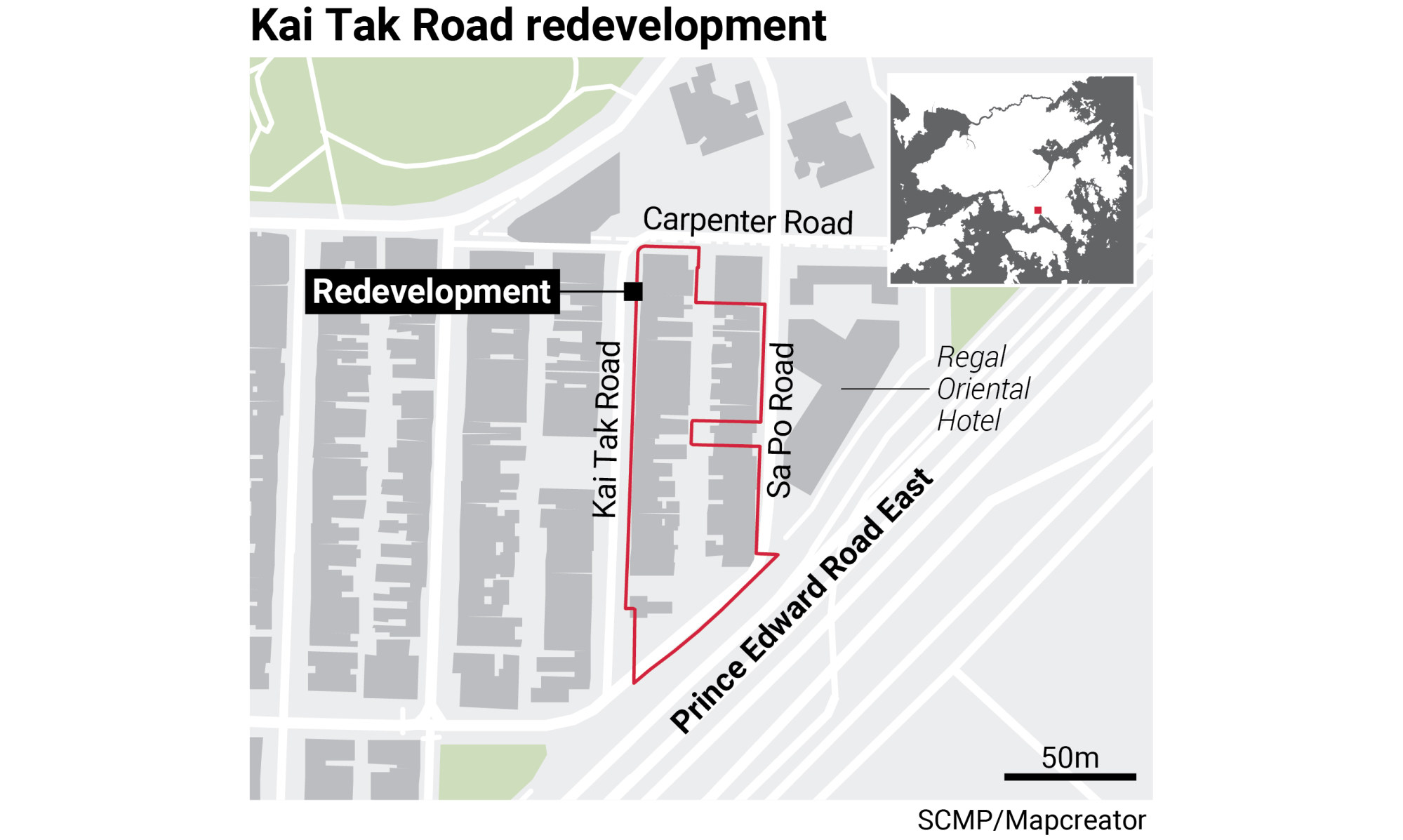

The project, launched by the Urban Renewal Authority (URA) in February, 2019, covers about 6,110 square metres along Sa Po Road and Kai Tak Road on the edge of Kowloon City. About 50 buildings, 50 years old on average, will be torn down, affecting about 370 households and nearly 1,000 people.

The URA’s current proposal is to redevelop the site to build 810 small and medium-sized homes, commercial areas, public amenities and community spaces. A split-level sunken plaza will link up with the underground pedestrian tunnel connecting the Kai Tak development area, which is now divided by a major highway. The project is targeted for completion by 2029-30.

The URA issued acquisition offers to affected property owners last October. Those eligible can sell their flats to the URA or swap those for ones in the redeveloped area or the Kai Tak Development Project. As of March 31, nearly 90 per cent of the affected property owners have accepted the acquisition offers, while 22 have chosen to swap their flats for ones at Kai Tak development area. The selection of flats will be carried out on April 29.

Tenants renting affected flats have been promised help too. On acquiring a property, the URA will provide those eligible ex gratia allowances and help with finding alternative housing. The URA says it will reserve public housing units for the affected tenants, including the area near the redevelopment site if there are vacancies, to help maintain their community network.

In Hong Kong’s ‘Little Thailand’ of Kowloon City, redevelopment brings fears for community

‘A place full of community spirit’

For those who have been in the area for decades, the idea of leaving is painful despite the rundown state of the buildings.

Kowloon City is known for its large Thai and Chiu Chow communities, and many of the Thais also have Chiu Chow roots.

In the early 20th century, Chiu Chow people, originally from eastern Guangdong province, migrated to Thailand and married Thais.

In the 1970s, many Thai-Chinese families came to Hong Kong, drawn by the city’s booming economy, and settled in Kowloon City, with its large Chiu Chow population in the infamous Kowloon Walled City, a sprawling complex of 350 slum buildings that were demolished in 1993.

Born and raised in Kowloon City, Hongkonger Leo Tong, 53, has lived within the redevelopment area for nearly 10 years, sharing a 300 sq ft flat along Kai Tak Road with his 76-year-old mother and younger brother, 48, paying a monthly rent of HK$8,000.

The former advertising designer, who lost his job last year, recalls a time when the area bustled with people drawn by Chiu Chow food or heading to the former Kai Tak Airport, before Hong Kong International Airport opened in Chek Lap Kok in 1998.

His mother used to live in the Kowloon Walled City, where a park now stands, a five-minute walk from their home.

Tong says the family’s deep connections in the area, with many of their relatives living nearby, make the thought of leaving hard to bear. His mother gets so worried she sometimes cannot sleep at night, he adds.

But their landlord has already sold the flat they are renting to the URA, and Tong hopes to get a public rental housing flat within the district.

“It is difficult to adapt to a new place, especially for the elderly,” he says. “This is not just a place where we live, but also a place full of culture and community spirit.”

Chalermporn Sajian has been running the FriendSHIP Thai restaurant at 38, Kai Tak Road for 15 years.

The 48-year-old father of three came to Hong Kong from Thailand in 1995 and toiled as a chef at the restaurant for eight years before taking it over in 2006.

He remembers the early days when his takings amounted to just HK$3,000 to HK$4,000 a day. But he worked hard, designing new menus and doing the cooking himself, to attract and retain customers.

Among the most popular items on the menu are beef in lemonade and raw prawn with fish sauce, he says. He now has five Thai employees helping him.

Urban Renewal Authority to build more than 3,000 flats at redeveloped Kowloon City site

Chalermporn says he has weathered the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic, but is worried that the URA plans may deal a lethal blow to his business.

He says it will be hard to find alternative premises at the right rent within Little Thailand, and fears he will lose his regular customers if he moves elsewhere.

“I feel uncertain about the future. I will be heartbroken to see all that I have built over the years flushed down the drain,” he says.

According to the 2016 population by-census, 870 Thai people lived in Kowloon City that year, out of a total of 10,215 Thais in Hong Kong.

Parichat Jaroennon, a 58-year-old domestic helper and vice-chairwoman of the Thai Migrant Workers’ Union, lives in Sai Kung but makes her way to the area on Sundays to relax and socialise. Many other Thais living in other parts of Hong Kong gather here on weekends too.

Her union, which has more than 300 members, is within the redevelopment area and she fears that relocation will make it harder to serve members.

“We come here when we get homesick. We are worried that our community will fall apart,” she says.

The URA says it will make special arrangements to preserve local characteristics in the redevelopment, including reserving units for Thai restaurants and long-established eateries, as well as organisations serving the Thai and Chiu Chow communities.

But in the absence of further details, those affected remain uncertain about what lies ahead. Restaurant owner Chalermporn says even if his eatery is eligible for a reserved unit, he cannot close his business and wait years for the redevelopment to be completed.

‘It’s not about money only’

Professor Ng Mee-kam, director of urban studies programme at Chinese University, says urban redevelopment is meant to improve the living environment, but in many cases, those directly affected by such projects in the city suffer from its impact.

Apart from those who must move out, she points out that those who stay behind are also affected by the changed cityscape, including increased living expenses in the redeveloped area.

She says the authorities should conduct a social impact assessment before redevelopment planning, to see what can be done beyond offering compensation, and to treat each project differently.

As for the plans for Little Thailand, she says: “It is probably the beginning of the dismantling of a once rather tight community … unless there is a U-turn to the government’s policy.”

Kowloon City district councillor Ma Hei-pang says the redevelopment project, like several others across his district, has not considered the impact on affected residents and communities.

Hong Kong’s Urban Renewal Authority plans to further develop Kowloon City

“The affected residents are labelled and measured by money,” says Ma, who is chairman of the district council’s Working Group on Concern over Urban Renewal. “The authority has a responsibility to help resettle affected residents within the same neighbourhood so they can continue enjoying their lives.”

A group of about 20 affected residents, business owners and volunteers formed the Kowloon City Redevelopment Concern Group in June, 2019, and after conducting surveys and consulting experts, proposed a land swap to enable residents and businesses to resettle within the district and preserve their community networks.

The proposal, released in February, urges the URA to swap its land in the To Kwa Wan redevelopment area for a plot in the Kai Tak development area under the Hong Kong Housing Society to rehouse the affected residents and businesses.

The group also wants the URA to swap its To Kwa Wan site with a plot of the same size for government, institution or community purposes next to the To Kwa Wan Sewage Treatment Works so affected car repair garages, hardware stores and craft shops can be relocated.

Both the URA and Hong Kong Housing Society have rejected the proposal, but concern group volunteer Gloria Chaung says she is not giving up yet and will stay open to suggestions. The group has garnered the support of about 130 residents and businesses within the redevelopment area and about 200 residents nearby.

“We hope to remind the authorities to consider the needs of those affected,” she says.

Fearing the worst will come to pass, Thai resident Wareerat has looked for flats elsewhere but found them either too small or too expensive.

Eager to remain in Little Thailand with her community, she says: “This place means so much to me.”